Category: Books

Publicity and book reviews. See right hand panel for Robin’s books ->

Primer for PLATONIC THINKING

Any attempt to ‘explain’ Plato will inevitably expose the cultural bifurcation caused by the split between what the modern world calls spirit and matter, that fundamental polarity that has lain deep and uneasily in human consciousness and whose duality has been fully played out during our Age of Pisces. From Classical Greece onwards, spirit and matter have been adversaries within a historical creation story, and mankind’s allotment has been to face and deal with this dual dragon, having the fiery breath of fundamentalist polarity, and has most recently chosen matter as its friend and abandoned spirit as superstitious.

Plato’s works are of crucial importance in describing a cosmology which offers humankind the chance to believe in and even interact with higher intelligences. In The Sleepwalkers, the materialist Arthur Koestler is not keen on Plato. He attacks him and Platonists in general for their non-scientific and passive view of the world, which he claims held back the ancient world even though those Greek empiricists appear to have kick-started both the scientific process and logical methodology remarkably well from the sixth to the fourth century BC.

Meanwhile, Richard Tarnas, in The Passion of the Western Mind, unlike Koestler, has read and understood his astrology and his metaphysics, is pro-Plato and places him as a philosopher who saw this possibility of building of a relationship with Higher Intelligence and that scientific experimentation is not the sole way forward if one wishes to understand the workings of the Cosmos.

To Plato, it hardly mattered if one improved one’s lot by understanding how a lever worked or what made an elephant able to stand up. What mattered was that one understood that all things ‘under the Moon’ belonged to the sublunary world representing the imperfect mortal world, a distortion or false picture of the cosmic perfection of Divine Mind. Man’s task was ultimately to be able to understand, even reflect back, that perfect Form, the creative Idea that lay behind mortal experience of the senses – the Form.

The Idea precedes the Form.

LAUNCH OF MEGALITH BOOK AT AVEBURY AND STONEHENGE, SUMMER SOLSTICE 2018

Wooden Books new compilation hardback, MEGALITH- Studies in Stone, was duly launched over the summer solstice celebrations at Avebury and at Stonehenge. The sun dutifully arose from a perfect azure sky at 4:52 am ( First Flash). Fabulous!!

Wooden Books new compilation hardback, MEGALITH- Studies in Stone, was duly launched over the summer solstice celebrations at Avebury and at Stonehenge. The sun dutifully arose from a perfect azure sky at 4:52 am ( First Flash). Fabulous!!

Continue reading “LAUNCH OF MEGALITH BOOK AT AVEBURY AND STONEHENGE, SUMMER SOLSTICE 2018”

New Edition of Stonehenge by Wooden Books

The new year has brought me an opportunity to revise and update the first edition (2000 AD) of Stonehenge, one of those little sparkly Wooden Books, a genre founded by John Martineau.

Continue reading “New Edition of Stonehenge by Wooden Books”

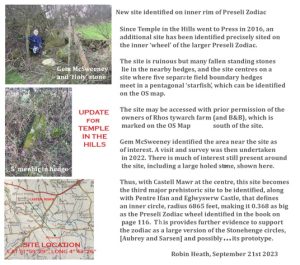

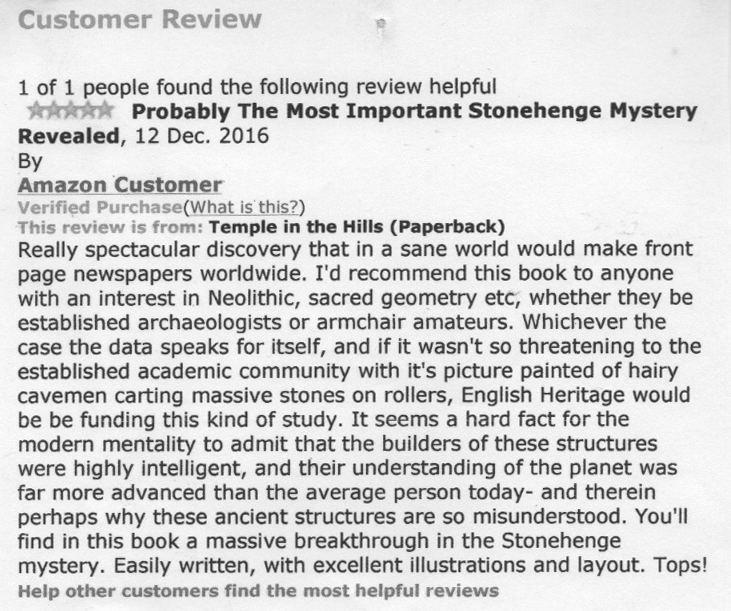

Amazon Book Review – Probably the Most Important Stonehenge Mystery Revealed

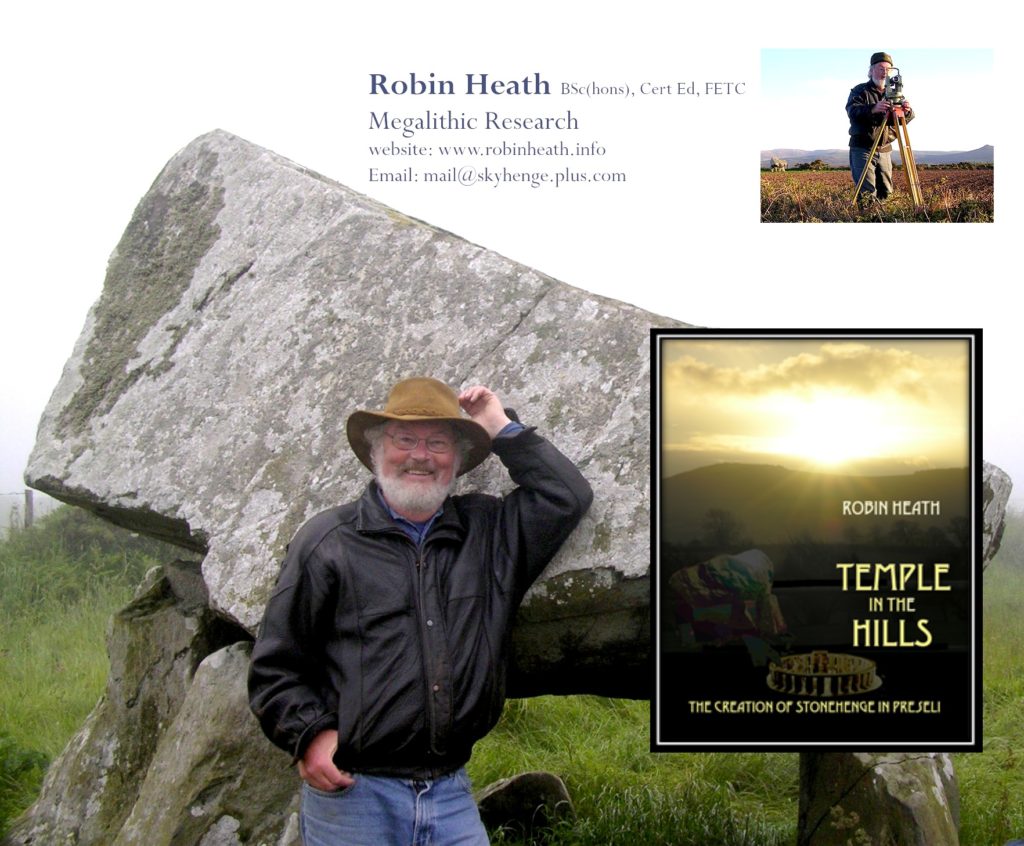

Below is a review of Temple in the Hills, given a five star rating by the reviewer. It’s better than any Easter egg. Half the print run has gone after five months and the book section lets you know how you may acquire a copy. An early chapter from this book is blogged earlier on this site.

Continue reading “Amazon Book Review – Probably the Most Important Stonehenge Mystery Revealed”

Read the first review of Temple in the Hills

The first review of my recent book, Temple of the Hills has been received from author and researcher Dr Thomas K Dietrich, whose most recent book, Temple of Heaven and Earth – Guide to Earth Energy & Inspiration at Sacred Sites was published by Save our Sacred Sites Society, San Bruno, California. It is a thorough and coherent account of the ancient roots of human encounters with what John Michell (in The View Over Atlantis) called ‘Spiritual Engineering’ and which has since come to be re-categorised as ‘earth energies’. A professional stone-image carver, once a student of the late Professor Rodney Smith during the 1960s, Dietrich has spent a lifetime reading ancient history, mythology and science, living in Ireland for thirteen years and travelling widely, investigating ancient sites throughout Europe, Corsica, Sardinia, Tenerife, Malta, Rhodes, Crete, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, the Red Sea, Israel, Jordan, in addition to the American Southwest, Mexico, Yucatan, Belize, Guatemala and South America, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru.

An active researcher, Dr Dietrich has written The Earth Holder (1983), The Origin of Culture and Civilisation (2005), The Culture of Astronomy (2011) and Temple of Heaven and Earth (2016).

Dr Dietrich is therefore among the rather too few people who are amply experienced and qualified enough to be able to write a critical review of my own work, for which I warmly thank him.

For more details of his research, visit his website cosmomyth.com

Photograph Two. Castell Mawr Henge. Larger than Stonehenge Over 500 feet ‘diameter’, this site sits perched on the flat summit of a rounded hill near Eglwyswrw, north of the Main Preseli ridge and off to the left of the dolmen in the previous photograph (Image via the wonderful Google Earth).

Book Review of Temple in the Hills

Hello Robin,

I thoroughly enjoyed Temple in the Hills, and many others will enjoy it also. Your excellent surveys are really the key to convincing archaeologists of the broad scope of ancient science and knowledge. I have attached a short review and do firmly believe that we should encourage students to follow your footsteps in metrological surveys so that more people may convince themselves of these essential sciences.

Best Regards and Thank you again for your inspirational book!

TKD

Thomas Karl Dietrich is the author of Temple of Heaven & Earth, Culture of Astronomy, and Origin of Culture. websites: cosmomyth.com and donohoememorials.com

Here is his review:

REVIEW

TEMPLE IN THE HILLS, The Discovery of the Original Stonehenge by Robin Heath

The introduction to Temple in the Hills by Robin Heath traces olden traditions and modern movements concerning the bluestone circle at Stonehenge, Zodiac hunters, New Age celebrities such as John Michell and Alexander Thom. The main corpus is dedicated to a review of astronomical phenomena and especially Heath’s discovery of the ‘Lunation Triangle’ within the context of ’the 30-segment, marked rope & peg’ configuration producing the 5-12-13 triangle which numerically defines the Moon’s relationship with Sun and Earth. Heath also gives a basic primer upon how to construct an accurate Equilateral Triangle on the landscape; again by simple rope & peg implements, showing that detailed, large-scale surveys may be achieved with very simple tools –proving that complex constructs were well within the abilities of our Stone-Age ancestors.

Robin Heath brings a solid case of evidence in favor of Neolithic metrology into the courtroom of archaeology. The evidence turns upon his measurements and discovery of ‘the Preseli Wheel’, centered upon the 500 foot diameter henge at Castell Mawr. Heath delineates five spokes of this wheel: Llech Drybedd, Carningli Summit, Foel Feddan, Carn Menyn, and Foel Drygarn which each average 18,630 feet (3.52 miles) upon the Preseli circle. The evidence of this wonderful precision is an indictment of modern archaeology’s continuing neglect to embrace and acknowledge metrological data and refined astronomical alignments. Heath returns to one of his 2010 investigations of his survey of the Preseli Vesica showing the distances between five locations upon a diamond pattern of two base-to-base equilateral triangles. The length of the common base and the sides of these two equilateral triangles show a nearly equal length and a mean distance of 11,759.0 feet demonstrating; in the author’s own words, “An accuracy that showed it to be a surveyed structure.”

Heath’s detailed demonstration of these irrefutable similar dimensions at the Preseli Wheel and Preseli Vesica represents no small contribution to science –because every well-documented opus elevates and substantiates the case for large-scale Neolithic metrology, precision alignments, as well as the broad based canons and traditions involving cycles, numbers, and geometry. It is absolutely important to celebrate this achievement for what it has and will accomplish. But, rather than bemoan the slow acceptance of new scientific data, I am quite sure that colleges and universities would take up such an interesting project for their students to gain valuable expertise in metrology; namely, to confirm Robin Heath’s survey measurements. This would once and for all guarantee the acceptance of accurate large-scale metrology in the Neolithic period and ignite a fire under the dragging feet and torsos of the archaeologists.

In his conclusion, Robin Heath presents the initial stages of his paramount discovery that the Aubrey Circle and the Sarsen Circle of Stonehenge bear the same relationship to one another as do the Preseli Wheel and its central circle around Pentre Ifan and Eglwyswrw. This correspondence shows that Stonehenge was based upon the template of the Preseli Wheel in Wales dated between 3200-3800 BC. Heath notices that genetic biologists conclude that the brain capacity of humankind has been more or less the same for almost 200,000 years. TKD

To purchase a copy of this book, full details are found in this category (Books) of the website.

Books by Robin Heath

from Bluestone Press, The Old Post Office, GLANRHYD, Cardigan, Pembs. SA43 3PA.

Bluestone Press was founded in 1993. All our titles are locally printed by Gomer Press, perhaps the best known publisher/printer in Wales. Our titles are traditionally designed books, printed onto high quality paper and sewn covers, and bound into soft back format. They last, and some. In addition to books by Robin Heath, Bluestone Press has also published specialist astronomy and astrology textbooks, audio books, soli-lunar calendars and leaflets on musical instrument restoration and megalithic site tour guides, in addition to postcards and gift cards.

Once payment has been made it is often possible to dispatch books within 24 hours. We like to know that they have been received safely, and we need to know if books have arrived damaged during transit.

There are substantial discounts for multiple book orders, for larger quantities and trade, please note that our distributors are all happy people.

www.robinheath.info. email : [email protected]

Bluestone Press Titles

- A Key to Stonehenge (1993), rev. 2nd edition 2005, Out of print.

- Sun, Moon & Stonehenge (1998) Out of print.

- The Measure of Albion (2004) (with John Michell) Out of print.

- Powerpoints (2007)*

- Alexander Thom : Cracking the Stone Age Code* (2008)

- Bluestone Magic : A Guide to the Prehistoric monuments of West Wales* (2010) Full colour.

- Proto-Stonehenge in Wales*(2014)

- Temple in the Hills: Discovering the Origins of Stonehenge (2016) Full colour.

Hodder Headline

- Stone Circles : A Beginner’s Guide (1999)

Wooden Books

- Sun, Moon and Earth (1999 etc), various editions and available in 10 languages

- Stonehenge (2000 etc), various editions and available in 4 languages

Adventures Unlimited Press (AUP)

- The Lost Science of Measuring the World (with John Michell)(2006) A facsimile US edition of The Measure of Albion.

Mythos Press

- The Secret Land (with Paul Broadhurst)

All Bluestone Press titles (marked above in bold and asterix) are available by post, as a soft cover edition.

ORDERING BOOKS

To order a book from this list, we will need the following information, by email or snail-mail :

- Your name, address, phone number and email address.

- A shipping address, if different from the address above in item 1.

- The title(s)of the book(s) you want to buy.

- Whether you want the book signed, and do let us know the name of any recipient to be mentioned for a book to be gifted.

email : [email protected]

- A nice person at Bluestone Press will then email or phone with a quote for the book(s), inclusive of postage and packing costs.

- You then have two options: either

- to pay via PayPal through [email protected] or

- issue a cheque payable to Bluestone Press for the full amount (including post and packing charges), posted to,

- Bluestone Press, The Old Post Office, GLANRHYD, Cardigan, Pembs. SA43 3PA.

Once payment has been made it is often possible to dispatch books within 24 hours. We like to know that they have been received safely, and we need to know if books have arrived damaged during transit.

There are substantial discounts for multiple book orders, for larger quantities and trade, please note that our distributors are all happy people.

www.robinheath.info. email : [email protected]

Those Old Preseli Blues

An excerpt from Temple of the Hills – The Discovery of the Original Stonehenge

by Robin Heath, Bluestone Press, 2016

Long lodged in folklore and myth there runs an ancient Welsh tradition telling of an original bluestone circle in the Preseli region of west Wales. The matter was referred to in The White Goddess, a seminal work by the Irish academic historian and poet Robert Graves (Faber, 1948),

‘It has been suggested that the smaller (bluestones) stones, which are known to have been transported all the way from the Prescelly Mountains in Pembrokeshire, were originally disposed in another order there and rearranged by the people who erected the larger ones. This is likely, and it is remarkable that these imported stones were not dressed until they were re-erected at Stonehenge itself.’

However, this tradition goes back much further than recent times, in essence the tradition is about a bluestone circle being uprooted from Preseli and taken in antiquity to Stonehenge, then reassembled as part of the monument that has stood on Salisbury Plain for at least five millenia, mute, magnificent and yet, above all, mysterious. And despite centuries of attention from all manner of specialisms, the purpose of Stonehenge still remains unclear. This monument’s many secrets and its extant bluestone circle still tantalize and taunt those who attempt to understand the history and purpose of this unique monument.

Unexpectedly, one might think, professional archaeologists are presently taking this tradition seriously, as if it were a prehistoric fact, and are combing the Preseli Hills in an attempt to discover the original location of this alleged bluestone circle. Why would they do that?

Why Preseli?

The archaeologists are the latest activity that feeds the bluestone tradition, adding to it more stepping stones across the wide river that separates Stonehenge fact from Stonehenge fiction. As for many other traditions, their recent activity is neither new nor is it unexpected. This mythic territory and this sacred landscape have both been visited before. But there are several good reasons why the Preseli hills have become the hot spot for this bluestone circle treasure hunt, the most important being that this landscape’s connection with Stonehenge has been greatly reinforced during the past century.

In June 1903, a geology professor called William Judd scrutinised the implications of the tradition in an article for The Wiltshire Magazine His scientific account of that year listed the difficulties that could be expected in attempting to transport bluestones from ‘a distant locality’ to Stonehenge. He also noted that the bluestones had been shaped and polished at Stonehenge after having been transported, forming the so-called ‘bluestone layer’ of chippings around the monument. Judd made the following astute comment,

‘The old tradition concerning Stonehenge is that it consisted of a circle of ‘bluestones’ which had acquired a certain sanctity in a distant locality, and had been transported from the original home of the tribe. If so, the stones, brought from so far away, would have been reduced to something like half their bulk…

Is it conceivable that these skillful builders would have transported such blocks of stone in their rough state over mountains, hills and rivers (and possibly over seas) in order to shape them at the point of erection? ’

Professor Judd did not link the source of the bluestone circle as being in the Preseli region. In 1903, that source was not known for sure, and nobody then could be certain where the ‘distant locality’ of that original bluestone circle might have been. This remains essentially true today, although within two decades of Judd’s work, much stronger evidence was produced to support why the bluestone circle at Stonehenge might have once been located in the Preseli Hills, even where it might most likely be found.

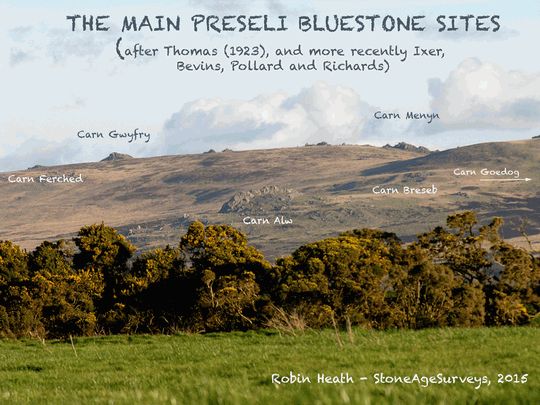

In 1923, a bright light was shone on what had previously been a rather nebulous tradition. Another renowned geologist Dr Hubert Thomas wrote the first scientific paper that supported a connection between the Preselis and Stonehenge. Thomas undertook a petrological analysis of the bluestones found at Stonehenge, enabling a crucial breakthrough to be made. The evidence suggested that these bluestones had almost all originated from a small collection of outcrops along the main ridge of the Preseli Hills, most notably the outcrops around Carn Menyn, a mile or so from Foel Drygarn, at the eastern end of the main Preseli ridge.

If there had ever been a bluestone circle installed in the Preselis, as the tradition suggested, Thomas provided good evidence to back up that possibility, and indirectly identified its location. His work forged a geological link between the Preselis and Stonehenge and although Thomas’s work had not directly mentioned the location of any bluestone circle, his paper undoubtedly was suggesting that were there ever such a monument, it would likely have been located near to Carn Menyn. In other words, Thomas had confirmed scientifically that an original lost bluestone circle could certainly be a possibility, and indirectly had suggested where it might best be found.

Thomas’s work represented a major breakthrough in understanding the origins and purpose of Stonehenge. It carved through many of the Dark Age and medieval elaborations of the original tradition, but it left untouched another story, linked to the 6th century Merlin, who told that the bluestones arrived at Stonehenge from the Wicklow hills in Ireland, by giants, and had been shipped over the sea on rafts, by giants who assembled them into Stonehenge. This variant of the original tradition was made very popular by the twelfth century chronicler, Geoffrey of Monmouth. His popular fourteenth century romance was later embellished, this famous artwork showing a giant placing a lintel onto a waiting megalith in order to complete the sarsen circle at Stonehenge.

Unfortunately, the geology is all to pieces here, for these are sarsen stones being depicted in this cartoon illustration from the period, not bluestones from Ireland or from anywhere else. The bluestones at Stonehenge are all much smaller than the incredulous mortals shown here watching the giant’s superhuman (and mechanically impossible) feat. However Geoffrey of Monmouth’s story does at least involve a sea journey during the transport of the stones.

Allegedly born in Carmarthen, an old Roman sea-fort less than 15 miles from the Preseli Hills, Merlin was brought up in that part of Wales two centuries after it had become an Irish colony, within a large part of southern and western Wales that spoke Irish. Whoever created this story, perhaps it was the late fifth-sixth century wizard, Merlin, who may have thought west Wales was Ireland!

This all becomes rather irrelevant however, simply because this tall story is not referring to the bluestones, but instead to the much larger sarsen stones, else Merlin’s giants would have come over as wimps and his story unlikely to impress anyone, for the average bluestone is a tenth of the size and weight of the mighty sarsen stones found at Stonehenge. Then as now, most people visit Stonehenge to see the sarsen circle and the trilithon horseshoe, the central part of the monument. It has been the logo for Stonehenge for a very long time.

There is also the not insignificant factor that no one can be certain whether Merlin actually existed or was simply a legendary folk hero. The Merlin story thus fails to convince as a credible explanation of the source of the bluestones at Stonehenge. However the narrative does link Stonehenge to a source of megalithic stones to the north-west of the monument and suggests they were transported by ‘giants’ rather than glaciers, and that the journey involved a sea passage. Geoffrey’s yarn is part of Stonehenge’s history, but it’s foggy message is confusing and gets us very little nearer the source of the tradition of a bluestone circle being moved to Stonehenge.

The Preseli Zodiac

During the 1970s an apparently new Preseli tradition concerning an ancient circle in the Preselis was placed into popular consciousness. This was a claim made by a group calling itself by the acronym IGR (Institute for Geomantic Research) for the existence of an ancient Preseli landscape zodiac. Just as was the case for the bluestone circle tradition, the idea of a prehistoric British landscape zodiac was anything but new, the concept permeating through the works of Taliesin and other great Bards. Welsh history does not go back much further than Taliesin.

Much more recently, in 1809, Welsh author Edward Davies published Mythology and Rites of the British Druids, which contained a powerful statement concerning the significance and purpose of landscape temples,

‘As the Britons distinguished the Zodiac, and the Temples or Sanctuaries of their Gods, by the same name of Caer Sidi, and as their great Bard Taliesin blends the heavenly and the terrestrial Sidi in one description, we may presume that they regarded the latter, as a type or representation of the former.’

The two component words that make up Caer Sidi, have a duplex meaning in Welsh, they refer to both the celestial zodiac and to temples consecrated to the ancient British gods. These two words are worthy of a better understanding. In Spurrell’s Welsh-English Dictionary of 1850, Caer is listed as meaning a wall, fortress, castle, fort, citadel, city. The milky way is cited as being Caer Gwydion, often known as Arianrhod.

The root sid- is clearly connected with spinning, weaving, rotation or wheels, and the list of words using this prefix is long. Sidell – fly-wheel; winder; whirl; whorl; rim of a wheel. Sidelliad – revolution; rotation. Sidellu – to whirl; to revolve; to rotate. Siddelydd – winder. Sidydd – zodiac. Sidyll – whirl; twirl; whorl; rim.

From this Welsh term to describe the celestial zodiac comes an important realisation. Any ancient British monumental circular structure is implicitly going to be a representation or reflection of the sky above, a celestial clock-face, a year-circle and a temple, a manifestation of As Above, so Below, as expressed in one of the tenets of the Emerald Tablet of Hermes, which may date from the seventh century, of similar age to the period of Taliesin.

‘That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above, working the miracles of one*.’

While it may be impossible to prove the veracity of that hoary tradition concerning the existence of a circle of bluestones once erected in the Preselis having been taken to Stonehenge, we can be a lot more confident that this circle, rim or wheel, had it ever existed, would have been understood by its builders to have represented a temple, and would have mirrored the zodiac or celestial sphere in some way.

To settle the matter would require that two things can be identified. Firstly, the site of the original (bluestone) circle must be located, a tall order, to put it mildly. Why? Because it would require that archaeologists find a stone circle somewhere in the Preselis where there are probably no longer any stones in situ, else it would have been identified a long time ago. By now it would be presumed to be solely defined by hidden but disturbed earth and in-fill debris where once there had been stones with socket holes. It would be like finding an empty packet of needles in a well-rotted haystack!

If and when located, their second task would be to understand the way that the zodiacal rim or circumference of this structure, the year-circle, was divided up. This cannot be undertaken by conventional archaeologists for they are not trained in, and do not have the required skills in recognising astronomical, geometrical or metrological patterns at prehistoric sites. And then there is the small matter that, for over a century, they have been trained to minimise the significance of prehistoric archaeoastronomy as a matter of course. To mention the father of modern archaeoastronomy, Alexander Thom, is to professionally fall on one’s megalithic rod (btw, that’s two and a half megalithic yards or 6.8 feet). So this second task, to understand the sky-circles, will have to be undertaken by someone who understands both megalithic science, zodiacs and year-circles. Guess who?

The 1970s quest for a Preseli zodiac can now be understood to be more obviously aligned with the present archaeological hunt for the original bluestone circle in Preseli. It is a shiny modern extension to the traditional ‘bluestone myth’, courtesy of Hubert Thomas’s petrological report from 1923, that originally impelled Lewis Edwards and later researchers of earth mysteries to visit the ‘Prescelly landscape’, in search of a landscape zodiac. And this same report almost certainly provided the initial impetus for the current archaeological froth of activity in Preseli.

From this short prologue a gambling man could reasonably predict that the Preseli bluestone myth may have a few more twists and turns left in the telling by the end of the twenty-first century.

Despite the Preseli zodiac remaining understood having become essentially a dismissed modern myth, it has been possible to demonstrate in only a few paragraphs that this modern myth has roots nourished by much older beliefs, and contains mythical elements that may go way back into the prehistoric period. In effect the myth of the Preseli Zodiac and the tradition of the bluestone circle collide and may be one and the same thing.

So here is the nub of the matter. Ancient traditions are rarely lacking in some core truth, however gaudy, evanescent and flimsy the wrapping paper may appear to suggest otherwise. Open up the package and this particular box is found to contain a tenacious legend about a sky-circle or zodiac or stone circle once built in the Preseli hills. Once the box has been opened up, the quest should then be to locate this hoary monument and try to work out who built it and why, and in so doing reveal its original purpose. It was identifying this task that originally impelled me to write Temple in the Hills, a project led me to the discover the original Stonehenge.

*************************

If you want to purchase a copy of Temple of the Hills by Robin Heath, please send an email to [email protected], with your name and shipping address, and whether or not you will want the book signed.

This will be acknowledged and the options of payment methods made available. Currently, these are £10 inclusive of P&P, in the UK, £12 in EU and £15 in US.

Other countries will require an appropriate shipping charge). The book contains over 80 original colour illustrations, including many of the Preseli landscape and its monuments.

Discovering the Original Stonehenge in the Preselis

Presentation Event at Castell Henllys on 19th October 2016, starting at 7:30pm

Presentation Event at Castell Henllys on 19th October 2016, starting at 7:30pm

Prehistoric archaeologists are currently focussing their attention on the Preseli region of West Wales. Why are they here, and what are they looking for?

The answer has to do with Stonehenge, 140 miles away in Wiltshire. Some of this mighty monument was constructed using bluestones that originated here in the Preselis. A fiery debate is raging about how they got there, whether they were taken by human toil or arrived on Salisbury Plain through glacial action.

So archaeologists are now looking for evidence of an original bluestone circle here in the Preseli hills, looking for surviving stones which, if they geologically match those at Stonehenge, will prove that human intent moved them there.

Robin claims to have recently discovered the original design for Stonehenge here in the Preselis, and has surveyed it using a theodolite. He will show this design has more to do with the Caer Sidi of Welsh legend, and the motions of sun, moon and stars, than it has with how a few bluestones ever found their way to Salisbury Plain.

In his illustrated and not too technical presentation he will also reveal that Stonehenge was a derivative taken from an original design conceived here in Wales, so how good is that?!

A graduate of UCNW, Bangor, Robin Heath was previously a research and development engineer with Ferranti, then a college head of technology department, late of Coleg Ceredigion. Since 1990, local author and presenter Robin Heath has been finding the prehistoric science embedded within the surviving megalithic monuments in Britain, Ireland and France. In 1993 Robin founded Megalithic Tours and has written ten books revealing evidence of high culture to be found in the astronomy, geometry and metrology of ancient artifacts. This material has been presented to students at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts, John Ruskin College, Brasenose College, Oxford, the British School of Dowsing, The Gatekeeper Trust, RILKO (Research into Lost Knowledge Organisation), and the Royal Institute of Mathematics.

A launch copy of Robin’s latest book, The Temple in the Hills, will be available at £10.

For more information and to make a booking contact Castell Henllys on 01239 891319

PRESS: Please contact Robin Heath by email (mail AT skyhenge.plus.com) for interviews or further information,